Engineering

The Theory of the Hydraulic Jump: Controlling Energy in Dam Design

01. Introduction

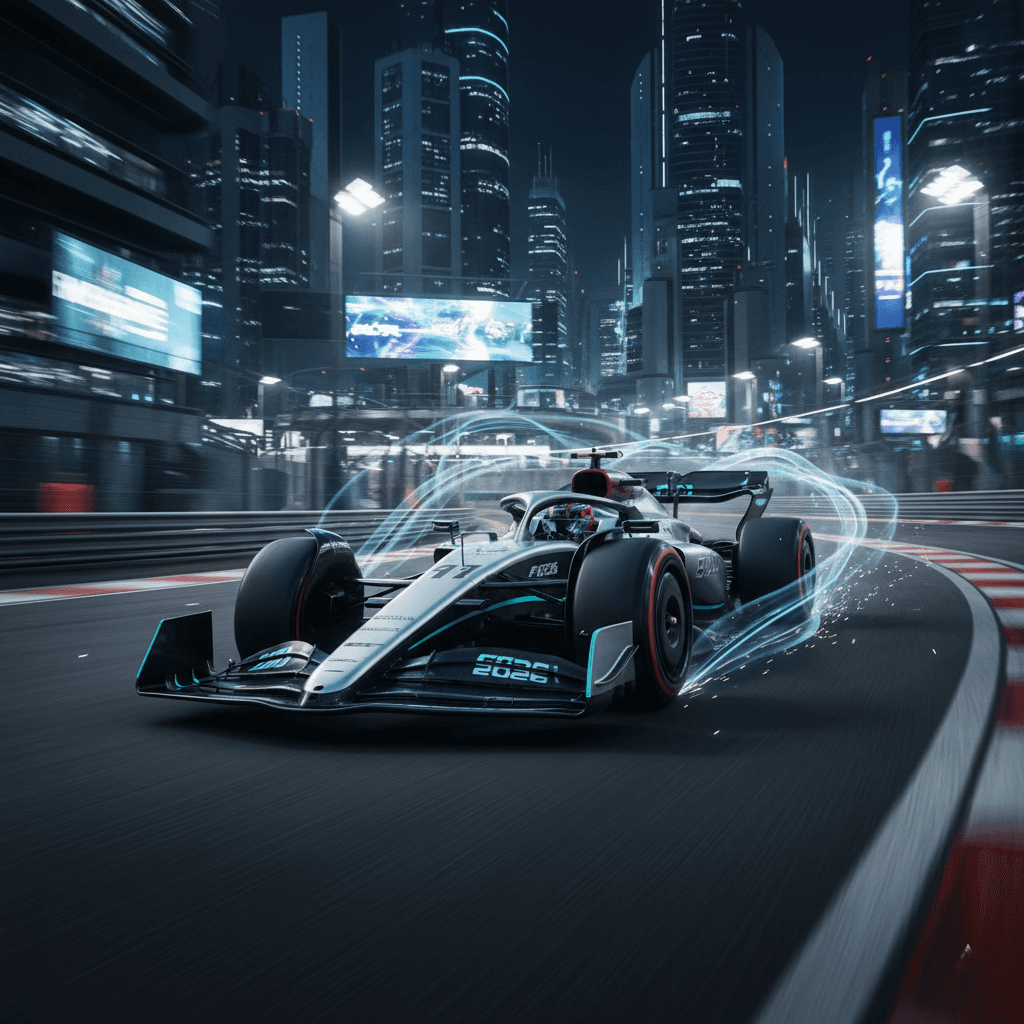

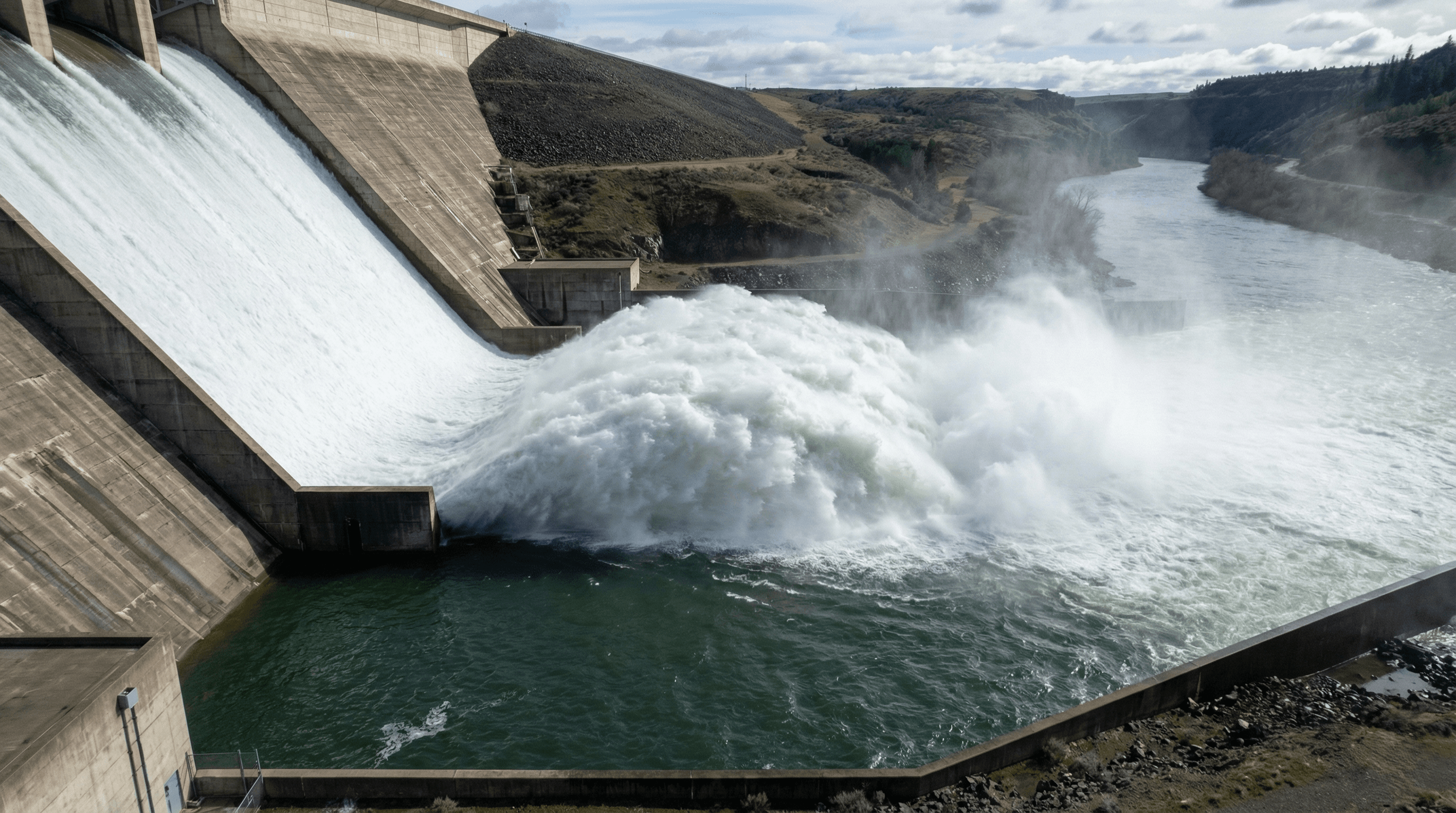

When you look at a massive dam, you will often see water rushing down a spillway at incredible speeds. However, at the bottom of that spillway, something strange happens: the water suddenly rises in a violent, turbulent "jump."

In fluid mechanics, this is known as a Hydraulic Jump. Theoretically, it is a "natural shockwave" in a liquid. It occurs when a high-velocity, thin layer of water suddenly slows down and transforms into a deeper, slower, and highly turbulent flow. For civil engineers, this isn't just a visual phenomenon; it is a critical tool used to dissipate (destroy) kinetic energy before the water enters a natural riverbed.

02. The Physics of Flow States: Supercritical vs. Subcritical

To understand the theory of a jump, students must first understand the two "states" of flowing water. These states are defined by the Froude Number (Fr), which is the ratio of inertial forces to gravitational forces.

1. Supercritical Flow (Fr > 1): This water is "fast and shallow." It moves at a velocity higher than the speed of a wave. In a dam, water on the spillway face is in this state. It contains massive amounts of kinetic energy that could easily erode soil and rock.

2. Subcritical Flow (Fr < 1): This water is "slow and deep."It is calm and stable. This is the state we want the water to be in before it travels further downstream.

The Theory: A Hydraulic Jump is the physical bridge that connects these two states. It is the only way for water to move from a supercritical state to a subcritical state (Chaudhry, 2022).

03. Why does the "Jump" Happen?

The jump occurs because of a conflict between momentum and pressure.

As water rushes down a spillway, it has high momentum. However, the river downstream is already full of slower-moving water. This slower water acts like a wall. When the fast-moving water hits this "wall" of slow water, it cannot continue at high speed.

Because water is incompressible, the kinetic energy (speed) has nowhere to go. It must be converted into potential energy (height) and thermal energy (heat through turbulence). This sudden conversion causes the water level to rise abruptly, creating the "jump" (Douglas et al., 2025).

04. The Critical Role of Energy Dissipation

The most important theoretical part of this topic for a civil engineer is Energy Loss.

If the water were allowed to hit the riverbed at the bottom of a dam at full speed, it would create a massive hole in the ground (scouring). Eventually, this would undermine the foundation of the dam and cause it to collapse.

Inside the hydraulic jump, there is intense turbulence and "eddy" formation (swirling water). This friction between water molecules converts a massive percentage of the water’s kinetic energy into heat and sound. While the water doesn't get "hot" enough for us to feel it, the energy lost is enough to protect the riverbed from erosion. This is why we build Stilling Basins concrete "rooms" at the bottom of dams specifically designed to force a hydraulic jump to happen safely (Hager, 2024).

05. Types of Hydraulic Jumps

Depending on the speed of the incoming water (the Froude Number), the jump can look very different. Engineers categorize them to understand how much energy is being destroyed:

- Undular Jump: The surface shows slight ripples. Energy loss is very low.

- Weak Jump: Small rollers form on the surface.

- Oscillating Jump: The water moves back and forth in a wave-like motion. This can be dangerous as it can damage the concrete walls of the basin.

- Steady Jump: This is the "perfect" jump for engineers. It stays in one place and dissipates energy very efficiently.

- Strong Jump: A very violent and rough jump. It destroys the most energy but requires a very strong concrete basin to contain it (Chaudhry, 2022).

06. Conjugate Depths: The Before and After

In theory, the depth before the jump (y1) and the depth after the jump (y2) are called Conjugate Depths or Sequent Depths. Even without doing the math, students should understand the relationship: if the incoming water is very fast and very shallow, the resulting jump will be very high. Engineers must ensure that the side walls of the stilling basin are high enough to contain this "Sequent Depth" so that the water doesn't flood the surrounding area (Hager, 2024).

07. Real-World Application: The "Baffle Blocks"

If you look closely at the bottom of a dam spillway, you will often see concrete blocks or "teeth" on the floor. These are called Baffle Blocks.

The Theory: These blocks are not there to stop the water. They are there to "trip" the water. They create extra friction and turbulence, ensuring that the hydraulic jump stays inside the concrete basin and doesn't slide further downstream into the unprotected riverbed (Douglas et al., 2025).

08. Conclusion

The Hydraulic Jump is a masterclass in the Law of Conservation of Energy. It shows how engineers use the natural laws of physics to control one of the most powerful forces on Earth moving water. By forcing water to "jump," we protect our infrastructure and ensure the safety of the environment downstream.

09. Bibliography

Chaudhry, M.H. (2022). Open-Channel Flow. 3rd edn. New York: Springer.

Douglas, J.F., Gasiorek, J.M., Swaffield, J.A. and Jack, L.B. (2025). Fluid Mechanics. 7th edn. London: Pearson Education.

Hager, W.H. (2024). Energy Dissipators in Hydraulic Engineering. 2nd edn. Zurich: CRC Press.

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (2023). Design of Small Dams. [online] Available at: https://www.usbr.gov/tsc/techreferences/mands/mands-pdfs/SmallDams.pdf [Accessed 31 Dec. 2025].

Test Your Knowledge!

Click the button below to generate an AI-powered quiz based on this article.

Did you enjoy this article?

Show your appreciation by giving it a like!

Conversation (0)

Cite This Article

Generating...