Engineering

The Return of the Combustion Engine: Exploring Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine (H2-ICE)

1.1 Introduction

The global engineering community is currently focused on a single goal: "decarbonization." The objective is to remove carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from transportation to combat climate change. For passenger cars, Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) are currently the leading solution. However, for heavy industries such as long-haul trucking, construction, and shipping batteries are often too heavy, take too long to charge, and do not provide enough range.

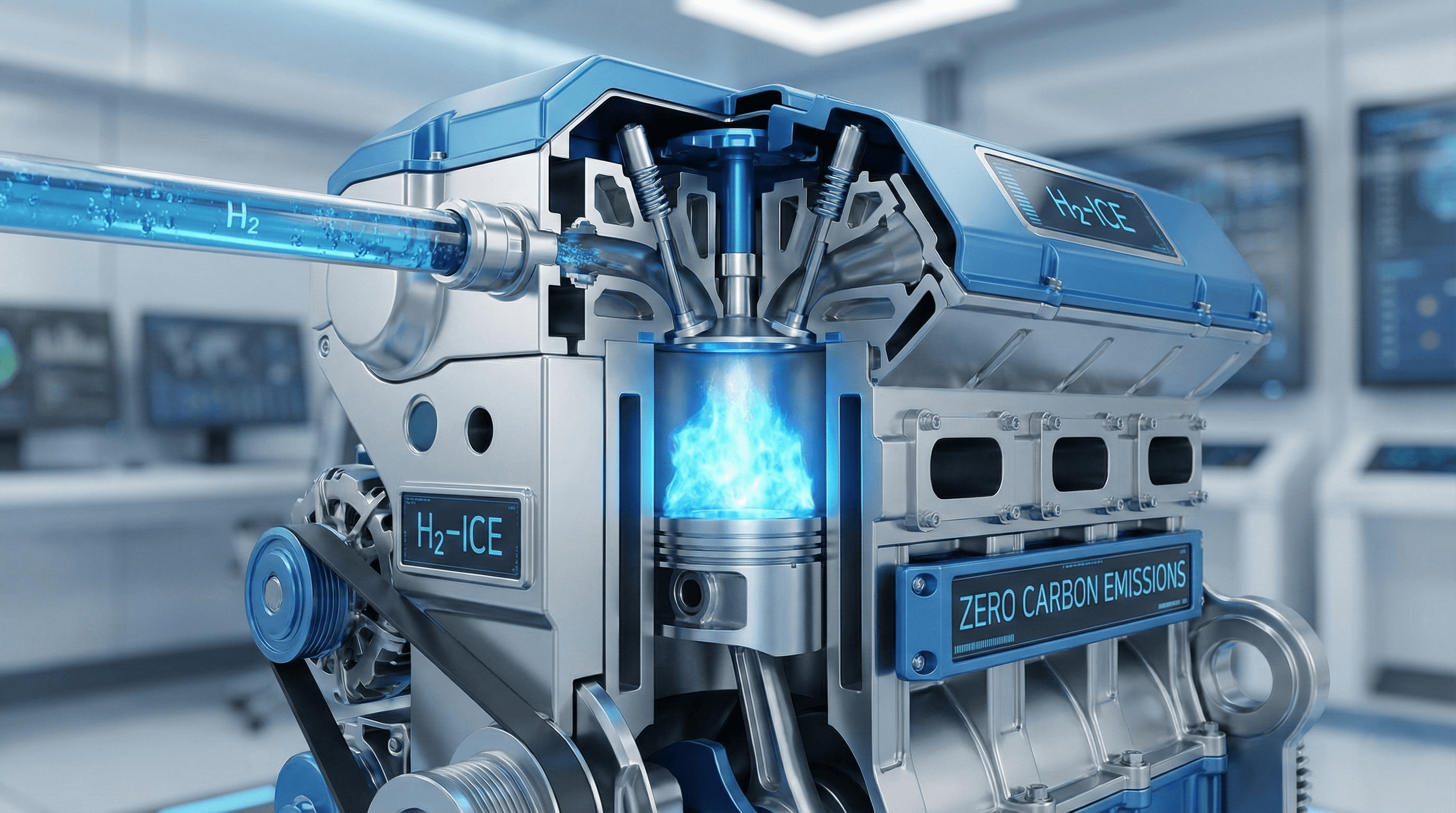

This has led engineers to revisit a technology that has existed for over 100 years: the internal combustion engine (ICE). The challenge is not the engine itself, but the fuel it burns. By replacing fossil fuels (petrol and diesel) with hydrogen, engineers can create an engine that looks and sounds familiar but emits almost nothing but water vapor from the tailpipe.

This technology is known as the Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine (H2-ICE). It is distinct from hydrogen fuel cells (FCEVs). While a fuel cell uses a chemical process to make electricity, an H2-ICE burns hydrogen to create heat and pressure, just like a traditional engine.

1.2 The Chemical Engineering of Hydrogen Fuel

To understand the engineering challenges of an H2-ICE, we must first understand the properties of hydrogen (H2) as a fuel. It is very different from gasoline.

The Advantages: The primary advantage of hydrogen is its gravimetric energy density (energy per kilogram). Hydrogen holds approximately 142 megajoules (MJ) of energy per kilogram. In comparison, diesel fuel only holds about 45 MJ per kilogram (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023). This means hydrogen is an incredibly potent fuel by weight. Furthermore, hydrogen does not contain carbon atoms. Therefore, when it burns (combines with oxygen), it cannot produce CO2. The primary byproduct of combustion is water (H2O).

The Disadvantages: The primary challenge is volumetric energy density (energy per liter). At standard room temperature and pressure, hydrogen is a very diffuse gas. To store enough energy to run a vehicle, it must be compressed to extreme pressures (often 350 to 700 bar) in heavy tanks, or cooled to cryogenic temperatures (-253°C) to turn it into a liquid (Toyota, 2024).

Furthermore, hydrogen has a very wide "flammability range" and burns extremely quickly and hotly. These properties make it difficult to control inside an engine cylinder.

1.3 How an H2-ICE Works

Mechanically, an H2-ICE is very similar to a standard four-stroke diesel or gasoline engine. It has pistons, cylinders, valves, and a crankshaft. The thermodynamic cycle is the same:

- Intake: Air and fuel enter the cylinder.

- Compression: The piston squeezes the mixture.

- Power (Combustion): The mixture is ignited, forcing the piston down.

- Exhaust: The burnt gases are pushed out.

Because the base architecture is the same, manufacturers can use existing factories and supply chains to build H2-ICEs. This makes them significantly cheaper to manufacture than complex battery systems or fuel cells (Cummins, 2023). However, because of hydrogen's unique chemical properties, critical components must be re-engineered.

1.4 Key Engineering Challenges and Solutions

Converting a diesel engine to run on hydrogen is not simple. Engineers face several significant technical hurdles.

1. The Problem of Pre-Ignition and Knock Because hydrogen burns so easily, it does not always wait for the spark plug to fire. Hot spots inside the cylinder such as a hot exhaust valve or residual heat from the previous cycle can ignite the hydrogen too early. This is called pre-ignition.

If the fuel ignites while the piston is still moving up during the compression stroke, it causes severe engine damage, known as "knock."

The Engineering Solution: To prevent this, engineers use Direct Injection (DI). Instead of mixing the hydrogen and air before they enter the cylinder (port injection), DI sprays the hydrogen directly into the combustion chamber at the very last moment before ignition. This means there is no fuel in the cylinder during the compression stroke to pre-ignite (JCB, 2023).

2. The Emissions Challenge: NOx It is often stated that hydrogen engines have "zero emissions." This is technically incorrect. While they produce zero carbon emissions, they can produce other pollutants.

Because the engine burns hydrogen using atmospheric air (which is almost 80% nitrogen), the high heat of combustion can cause the nitrogen and oxygen in the air to react. This creates Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), which are harmful pollutants regulated by governments.

The Engineering Solution: Engineers solve this by running the engine "lean." A "lean burn" means filling the cylinder with far more air than is necessary to burn the fuel. The extra air absorbs heat, lowering the combustion temperature below the point where significant amounts of NOx form. Any remaining NOx can be cleaned up using a standard catalytic converter in the exhaust system (Cummins, 2023).

3. Material Embrittlement

Hydrogen atoms are the smallest in the universe. They can actually diffuse into the metal structure of the engine components, particularly high-strength steel. Over time, this makes the metal brittle and causes it to crack. This phenomenon is known as hydrogen embrittlement.

The Engineering Solution: Engineers must select materials for fuel injectors, valves, and pistons that are resistant to chemical attack from hydrogen, often using specialized coatings or lower-strength, more ductile metals where possible.

1.5 The Future Role of H2-ICE

It is unlikely that H2-ICE will power personal cars in the future; battery electric vehicles are already highly efficient for that application.

However, H2-ICE is viewed as a critical "bridge technology" for heavy industries. A large excavator on a construction site or a semi-truck driving 1,000 km a day cannot easily stop to charge huge batteries.

Companies like JCB (construction equipment) and Cummins (heavy truck engines) are heavily investing in H2-ICE. They argue that it offers the durability of a diesel engine and the quick refueling time of traditional fuels, but without the carbon footprint (JCB, 2023).

1.6 Conclusion

The Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine represents a fascinating adaptation of mature technology. By applying modern mechanical and chemical engineering principles to a 150-year-old invention, engineers are finding ways to decarbonize the most difficult sectors of the transport industry. While challenges regarding fuel storage and NOx emissions remain, H2-ICE proves that the combustion engine may still have a vital role to play in a sustainable future.

1.7 Bibliography

Cummins (2023). Hydrogen internal combustion engines and fuel cells. [online] Cummins Inc. Available at: https://www.cummins.com/news/releases/2023/03/27/cummins-showcases-fuel-agnostic-engine-platform-conexpo-2023 [Accessed 27 Dec. 2025].

JCB (2023). JCB’s Road to Zero: Hydrogen Combustion Technology. [online] JCB.com. Available at: https://www.jcb.com/en-gb/campaigns/hydrogen [Accessed 27 Dec. 2025].

Toyota (2024). Hydrogen: The future of fuel. [online] Toyota Europe. Available at: https://www.toyota-europe.com/electrification/hydrogen [Accessed 27 Dec. 2025].

U.S. Department of Energy (2023). Hydrogen Fuel Basics. [online] Energy.gov. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-fuel-basics [Accessed 27 Dec. 2025].

Test Your Knowledge!

Click the button below to generate an AI-powered quiz based on this article.

Did you enjoy this article?

Show your appreciation by giving it a like!

Conversation (0)

Cite This Article

Generating...

.png&w=3840&q=75)